With “The

Branches of Time,” I want to take a slightly different approach from my usual

review and summation of a tale. Ironically, it was an editor’s note that gave

me the inspiration.

This post

explores David R. Daniels’ “The Branches of Time”—a thoughtful, deep-dive of a

time-travel tale from a little known author. The editors of Wonder Stories included a statement

alongside the story to express their opinions.

To say that

this short story contains some revolutionary time-travel theories would be

putting it exceedingly mild.

When the author, new to our magazine, submitted this story to us, his

accompanying letter stated that in it he had settled the time-travel question

once and for all. We must admit that a broad, unbelieving grin spread over our

countenances when the author dared make this assertion.

BUT—the smile soon left our faces after we had perused well into the

yarn—for, to our chagrin, Mr. Daniels had really propounded so many brand new

ideas about time and time-travel, and such logical ones—that he has not left one loophole in his argument!

You are perhaps smiling at this, as we did at first, but all we ask of

you is to read the story, which task you will not find hard, for it is filled

with as many thought-provoking theories as any science-fiction novel you have

ever read and you will sit for long after finishing it, pondering upon the

fantastic possibilities of this new kind of time-travel…

Page 295

§

“The

Branches of Time,” written by David R. Daniels,

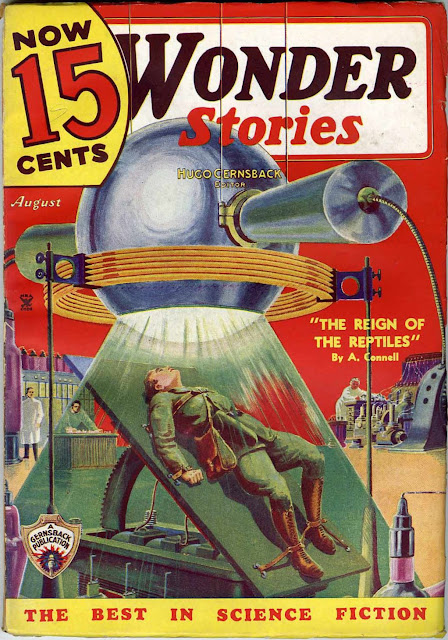

initially appeared in the August 1935 (volume 7 Number 3) issue of Wonder Stories.

Both the

editors and I initially viewed the story through the lens of mere time-travel

fiction. Only later came the realization of just how extremely unlikely it was

that a 20-year old would be well-versed enough (with Ph. D.-level physics) to

condense contemporary time-travel theories into a short story for a pulp-sci-fi

magazine’s audience. Particularly, since the physics describing what is

happening in the story would only be made public 22 years AFTER “The Branches

of Time” had been published.

David R.

Daniels was born in 1915 (though there is some question to this) and died on 17

April 1936. He is credited with publishing six short stories/novelettes; five

appeared in Astounding Stories and

one (“The Branches of Time”) in Wonder

Stories. Each of his tales, with the exception of his final, appeared in

1935.

Daniels

died, under questionable circumstances, from a self-inflicted gunshot wound;

either via accident or suicide.

Daniels was

21 years old.

§

There is

almost no biographical information readily available on Daniels. I could not

ascertain, where he was born or even where he died, with any certainty. There

is, however, one source that purports to reveal the grave marker of a David R.

Daniels who is buried in Ignacio Cemetery East in

If this

record is to be believed, this David R. Daniels was born in 1914, not 1915 (no

month or day) in

§

Amazing Stories, by Hugo Gernsback, was among the first science fiction pulp magazines

and began publication in 1926. After he lost Amazing Stories to bankruptcy, he founded Wonder Stories in 1929. Wonder

Stories was an early science fiction magazine that appeared under several

titles from 1929 through 1955. In 1936, Gernsback sold Wonder Stories to Beacon Publishing under the new title, Thrilling Wonder Stories. This title

continued publication until the end of 1955, when it ceased due to the decline

in the pulp magazine market.

The Pulp Magazine Archive at archive.org is a truly comprehensive source

for pulps. In addition to countless other pulp magazines, it contains a good

portion of the Wonder Stories print

run in PDF format.

§

Synopsis:

James Bell

and the narrator are two friends from school who haven’t seen each other in

years.

Millions upon

millions of years later,

So far, “The

Branches of Time” is a pretty

straight-forward time-travel-type tale. But, now it takes a significant turn.

As

I think so,

too.

§

From this

point on, I want to cease my detailed summation of the tale and instead, focus on a concept first put forth by

As

. . . the

world has innumerable dimensions in the Cosmos, and that each one of those

dimensions seems very different to us who see only three dimensional cross-cuts

of them at a time. We and our world

are like things seen by some one dimensional being. What, for instance, could

such a creature make of an automobile, being able to see no more than a line

along its surface. That’s how we look at infinity.

I live, and

yet I’ve seen the world which is this planet peopled by nothing besides races

of reptiles, a world into which I couldn’t possibly be born. And probably

somewhere—in the Cosmos—there is a me,

a James Bell who never invented a time-machine, but lived a normal

twentieth-century life as the other men around him did. However, I know nothing

of that, since at present—in absolute time— the ego-which-I-am inhabits the

body of the

But that

there are other Bell-egos, I know. For instance, there was the me I took the

revolver from. Both men were

Very

probably there is a you, John, who has traveled in time with me, whether you

ever do in this consciousness of yourself or not. And as far as that goes,

there may have been a planet Earth which fell into the sun ere it cooled, or

was stolen by a passing star.

Well, this

absolute theory of time-traveling, which must be the right one, takes away

certain of the paradoxes which have baffled imaginative people.

(Page 302-303).

I would like

to draw the reader’s attention to the third paragraph from the above quote that

begins “But that there are other . . .” In particular, I want to highlight the sentences:

“Both men were

Two

individuals, who up to some previous point in time, had been one and the same

being.

Holy Smokes!

This is Many-Worlds! More than 20 years before

§

As “The

Branches of Time” wound down to its conclusion, Bell stated to his friend that

he intended to travel into the far future where he hoped to encounter beings

that could satisfy his questions concerning the nature of reality and time. As

it turned out, if

Of course, I

am being flippant here. But this does provide a neat segue into what did occur

in 1957.

A widespread

and common definition (or explanation) of The Many-Worlds Interpretation is:

. . . an

interpretation of quantum mechanics that asserts the objective reality of the

universal wavefunction and denies the actuality of wavefunction collapse.

Many-worlds implies that all possible alternate histories and futures are real,

each representing an actual "world" (or "universe"). In

layman's terms, the hypothesis states there is a very large—perhaps

infinite—number of universes, and everything that could possibly have happened

in our past, but did not, has occurred in the past of some other universe or

universes.

The

Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics was first laid out by Hugh Everett in his

§

I believe

there are several relevant points concerning

Hugh Everett

was born in 1930. He wrote, in 1955 and presented in 1957, his dissertation

introducing the Many-Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Yet, it would

not be until 1976, when general readers and especially readers of science

fiction were introduced to

It is not known whether

All this is fascinating from a

history-of-science perspective. But, it still does not address Daniels and his

relation to the origin of the Many-Worlds Interpretation. Therefore, I propose that the ideas or

concepts underlying the Many-Worlds Interpretation were percolating in the

popular zeitgeist, especially in the realm of pulp science fiction. Thus,

almost making the appearance of the Many-Worlds Interpretation as a formal

scientific theory seemingly inevitable.

But when did

it all start? In the aforementioned biographical sketch, it is reported that

the earliest known example of a story referencing ideas or concepts that would

become Many-Worlds was 1938. It states: “As usual, it seems that writers

invented it all before the scientists. Fans have found in a 1938 story by half-

forgotten . . .” Moreover, the statement continues by claiming that these early

stories, and the ideas espoused: “. . . were more anti-Everettian than either pre-

or pro-Everettian . . .”

Please

recall Daniels’ “The Branches of Time” was published in 1935. His notions of

what-would-be Many-Worlds far predate any other such tale in pulp sci-fi, to

the best of my knowledge. And not only that, he does it by presenting a

uniquely positive take on

§

Once again,

very briefly (extremely basically) and in my own words, The Many-Worlds

Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics implies the entire universe is

fundamentally connected on a quantum level. Extrapolating from that, when

confronting a choice—left or right, let’s say—only one choice can be taken.

However, Many-Worlds Theory postulates that while one may determine to go left

(continuing the example above), in an alternate universe/reality, one may

determine instead to go right. From that point of determination, a new and

wholly separate universe is split off.

The illustration above is an excellent visual

representation of what I am talking about. From a place of decision, a split

occurs, with a new reality encompassing each possibility and with each reality

distinct from each other.

In essence,

this is The Many-Worlds Theory. And, this is exactly what Daniels has his

protagonist,

§

In many

ways, “The Branches of Time” is a very enjoyable time-travel tale. But, there

is a lot more going on here as the editors pointed out. Those editors realized

they had something special.

In addition,

I believe this tale laid the groundwork for many subsequent time-travel tales,

especially those that draw heavily from our current understanding of quantum

mechanics and do not rely upon some mysterious technology to explain the means

of time travel. In particular, I am thinking of Blake Crouch’s Dark Matter: A Novel from 2016. And, of

course, Stephen King’s 11/22/63: A Novel

from 2011. . .

Good

Evening.

References

Print

Resources

Digital

Resources

Daniels, David R. “The

Branches of Time.” Wonder Stories.

Continental Publications. August 1935. Volume 7 Number 3. [PDF file]. https://archive.org/details/Wonder_Stories_v07n03_1935-08/mode/2up

Online

Resources

Find a Grave, database

and images (https://www.findagrave.com : accessed 13 August 2020), memorial page for

David R Daniels (1914–1936), Find a Grave Memorial no. 67888599, citing Ignacio Cemetery East, Ignacio, La Plata County, Colorado,

USA ; Maintained by Frank Klein (contributor 47200843) .

Shikhovtsev, Eugene.

“Biographical Sketch of Hugh Everett, III.”

MIT Kavli Institute for

Astrophysics and Space Research. 2003. Web. 09 August 2020. https://space.mit.edu/home/tegmark/everett/

Shoemaker, Dave. “The Many

Worlds Theory is Wildly Fascinating.” Shoe:

United. WordPress.com. 08 August 2017. Web. 10 August 2020. https://shoeuntied.wordpress.com/2017/08/08/the-many-worlds-theory-is-wildly-fascinating/

Von Ruff, Al. “Summary Bibliography: David R.

Daniels.” The Internet Speculative

Fiction Database. ISFDB. Web. 5 August 2020. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/ea.cgi?1771

Von Ruff, Al. “Title:

TheBranches of TIme.” The Internet

Speculative Fiction Database. ISFDB. Web. 5 August 2020. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?87537

Wikipedia contributors.

"Many-Worlds interpretation." Wikipedia,

The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 12 July 2020. Web.

30 July 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Many-worlds_interpretation

Wikipedia contributors.

"Wonder Stories." Wikipedia,

The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 09 July 2020. Web.

11 August 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wonder_Stories