Horror fiction takes many forms – from the long, slow build-up to the short, sharp shock. Much of what I have commented on previously has been of the longer, more detailed variety. And, while I will continue to examine such works, I turn now to the pages of Weird Tales magazine for a dose or two (or more!) of the short, sharp shock.

§

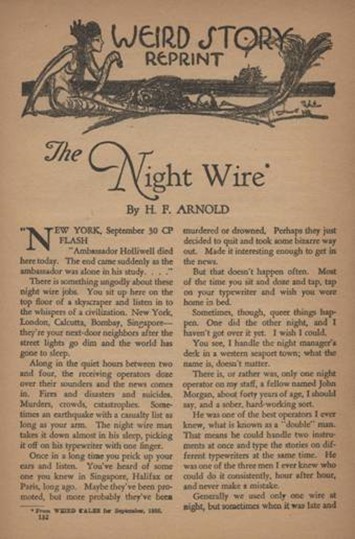

There is something ungodly about these night wire jobs. You sit up here on the top floor of a skyscraper and listen in to the whispers of a civilization. New York, London, Calcutta, Bombay, Singapore—they’re your next-door neighbors after the street lights go dim and the world has gone to sleep. [page 132]

§

“The Night Wire,” written by H. F. Arnold, first appeared in print in the September 1926 issue of Weird Tales (v08 n02). “The Night Wire” was also reprinted in the January 1933 Weird Tales (v21 n01).

§

Weird Tales is an American pulp magazine specializing in horror and fantasy. It was founded in late 1922 with its first issue dated March 1923. Weird Tales was known for printing works of H. P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard, Seabury Quinn, Robert Bloch and many, many other notable genre authors.

Plagued throughout its existence with financial woes, Weird Tales ended its initial publication run in 1954; though subsequently there were several attempts to restart the magazine. The current incarnation’s latest issue was dated Spring 2014.

A truly comprehensive source for pulps is The Pulp Magazine Archive at archive.org. In addition to countless other pulp magazines, it maintains a sizeable percentage of the Weird Tales print run in pdf format. However, in this case, the Archive failed me. The September 1926 issue is one of the few issues missing from the Archive. Fortunately, the Archive did have the January 1933 issue—on which this blog post is based.

§

H. F. Arnold is seen as a so-called “lost” author from the early days of Weird Tales and other pulps. One of the very few certain facts known about him is that three and only three of his tales were published:

“The Night Wire” in Weird Tales (Sept. 1926; reprinted Jan. 1933)

“The City of Iron Cubes” (two-part) in Weird Tales (Mar. & Apr. 1929)

“‘When Atlantis Was’” (two-part) in Amazing Stories (Oct. & Dec. 1937)

And that was it. No more.

However, I did come across recently published online sources that provided what I consider to be reliable biographical information on H. F. Arnold. According to these sources, Henry Ferris Arnold, Jr. was born on January 2, 1902 in Illinois. He graduated from Knox College with a degree in science.

He served in the military from 1942 under General Patton and was wounded in battle. He was discharged in 1947. Following his military service, Arnold lived in California until his death. On December 16, 1963, H. F. Arnold died as a result of an accident in his home.

None of the several occupations that he held throughout his civilian life indicated any type of literary interest.

§

“The Night Wire” is a powerful piece of weird horror fiction. Taking place over the span of one night where the night manager of a newswire service (the narrator) and his assistant—the only two in the office—experience something unearthly and truly disturbing.

§

Reports of the terrifying occurrences at the town of Xebico and the piecemeal nature in which its fate is revealed only heighten horror and confusion in the reader. The mysterious environment, its otherworldly setting and the lethal nature of the fog call to mind Stephen King’s The Mist and John Carpenter’s The Fog. While there is no direct evidence that “The Night Wire” was an inspiration or influence on those works, the similarities are hard to ignore.

§

I love the early days of pulp horror in particular the stories in Weird Tales. Weird Tales was masterful in its delivery of the short, sharp shock and “The Night Wire” is a superb example of this. A favorite of mine, “The Night Wire” packs a punch all out of proportion with its length. This post, and others in this occasional series, will focus on such stories found in the pages of Weird Tales.

References

Print Resources

Digital Resources

Arnold, H.F. “The Night Wire.” Weird Tales. Popular Fiction Publishing Company. January 1933. Volume 21 Number 1. [PDF file]. https://archive.org/details/Weird_Tales_v21n01_1933-01_LPM-URF-AT-SAS

Online Resources

Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com : accessed 26 January 2019), memorial page for Henry Ferris Arnold, Jr (2 Jan 1902–16 Dec 1963), Find A Grave Memorial no. 3385257, citing Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, San Diego, San Diego County, California, USA ; Maintained by Jim Ferris (contributor 46557174) .

Hanley, Terence E. “H. F. Arnold (1902-1963).” Tellers of Weird Tales. Blogger.com. 21 December 2018. Web. 26 January 2019. https://tellersofweirdtales.blogspot.com/2018/12/hf-arnold-1902-1963.html

Neslowe, E. B. “The Night Wire (1926) by H. F. Arnold.” Sepulchral Stories. Blogger.com. 27 December 2014. Web. 22 January 2019. http://sepulchralstories.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-night-wire-1926.html

Speller, Maureen Kincaid. “The Weird – The Night Wire – H. F. Arnold.” Paper Knife. Wordpress. 02 January 2012. Web. 28 January 2019. https://paperknife.wordpress.com/2012/01/02/the-weird-the-night-wire-h-f-arnold/

Von Ruff, Al. “Publication: Weird Tales, January 1933.” The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. ISFDB. Web. 22 January 2019. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?61951

Von Ruff, Al. “Summary Bibliography: H. F. Arnold.” The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. ISFDB. Web. 22 January 2019. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/ea.cgi?18253

Von Ruff, Al. “Title: The Night Wire.” The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. ISFDB. Web. 22 January 2019. http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?86054

Wikipedia contributors. "Weird Tales." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 13 January 2019. Web. 20 January 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Weird_Tales